History and Data

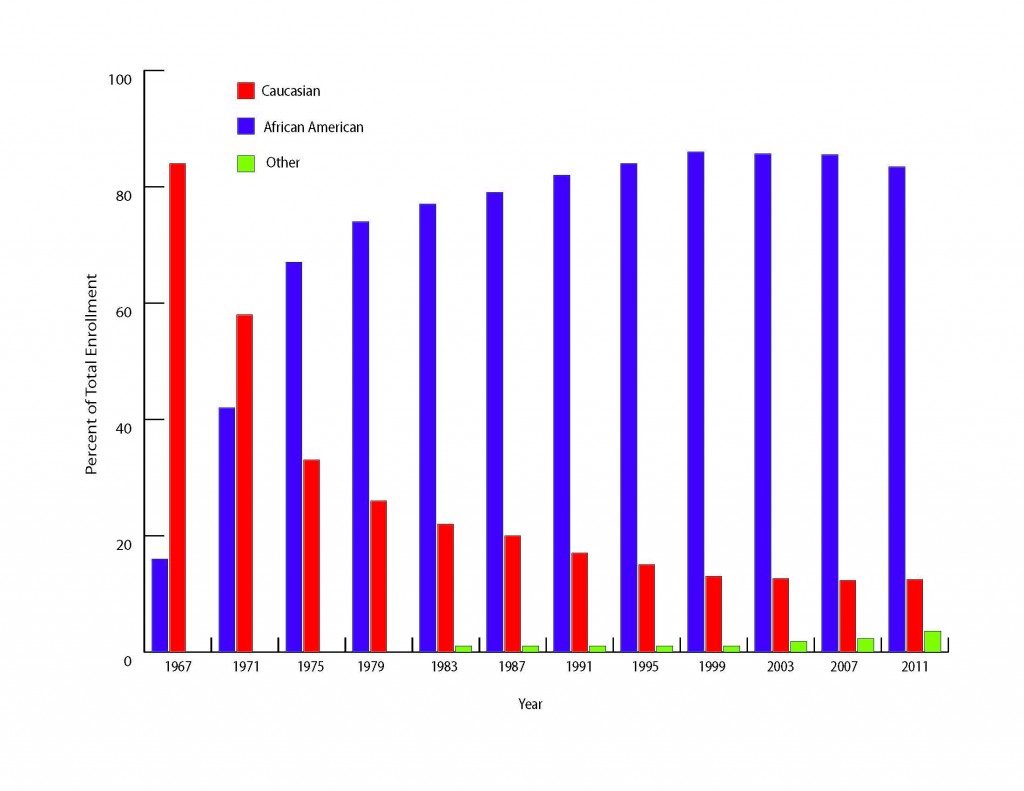

Although segregation became unconstitutional in 1954 with the Supreme Court ruling Brown v. Board of Education, U. City didn’t begin to keep records of student racial populations until 1967. In 1966, only seven African Americans are seen in U. City’s yearbook; before that there were none pictured. This, however, does not mean that no African Americans attended U. City High until 1966. Holston Black, parent of a former U. City student and a strong local advocate for African American achievement, said that after Brown vs. the Board of Education, “there was at least one or two [African Americans attending U. City High].”

U. City went from an all Caucasian school in 1965, with a few possible exceptions, to a currently almost all African American school. Black explained that “housing patterns establish a lot of the problems we have today.” He specifically mentioned redlining and “white flight.” Redlining occurs when banks and insurance companies identify an area by the ethnicity of its residents and discriminate against them, often refusing to provide insurance and mortgages to everyone in this area. Later ruled illegal, redlining was a common practice in the 1960’s.

“What the U. City city council did was put out an ordinance that forbade people to put up ‘for sale’ signs. Caucasians were getting afraid and moving out,” said Black of the city’s attempt to reduce redlining. The Supreme Court disapproved of this, however, and “for sale” signs were allowed again.

District Boundaries

“I don’t see where it’s any better now than when it was 60 years ago,” said Black. “The majority of the problems that were present before are still present today.”

University City’s current population, 44.2 percent African American and 49.6 percent white, indicates there should be a larger white population attending the high school. However, Caucasians only make up 15 percent of students in U. City’s school district.

“Caucasian people who have money don’t want to send their kids to a school where there are a lot of fights and not a lot of focus on education,” said senior Shayla Jackson.

The general perception in the community is that U. City is full of drugs, fighting, and a lack of academic focus, which explains why many U. City residents send their children to private schools.

“Certainly you can get a fine education at U. City High, but it’s hard to understand that if you look at the data that is published,” said Ellen Bern, U. City school board member. “Historically we have not done a good job marketing ourselves and we need to promote the many positive things and address our weaknesses.”

Black takes it one step further and refers to the education at U. City as “the least expensive private school in the country.” He feels students would receive the same education they would at John Burroughs or Clayton if they remained in U. City, and they wouldn’t have to pay any extra price for this quality education. The perfect example of this theory is his son, who went to Princeton University after graduating from U. City in 1984, in addition to scores of other students who attend prestigious universities, such as Elliot Wilson, class of 2011, who is currently attending Harvard and twins Justin and Julian Nicks, class of 2009, who attend Washington University.

Further complicating the issue is the fact that the city is basically divided at Olive Boulevard by race and income level. This dividing line separates Flynn Park and Jackson Park from Pershing and Barbara C. Jordan elementary schools.

Perceptions about student achievement vary from school to school. Kaicee Woods, junior, says that people’s perceptions about students who attended Jackson Park and Flynn Park are different.

“They think that where you live and where you come from determines how you act and who you are,” said Woods.

The demographics of the individual district schools begin to shift once students enter middle school.

“About three-fourths of the white students in my class left the district by seventh grade,” said senior Emma Mutrux.

Woods said that in elementary school she was friends with mostly white students. Now that Woods is a junior at U. City, she is friends with both white and black students.

“It looks like it’s a white and black issue, but it’s a socioeconomic issue,” said Bern.

Sixty percent of the students at U. City receive free or reduced lunch, which is proven to have an effect on academic achievement.

“You see that… people who have reduced lunch don’t take as many AP classes,” said Jackson.

In 2007, 14 African Americans were enrolled in AP classes and 28 Caucasians. This year’s AP enrollment shows 72 African Americans taking AP classes and 33 Caucasians, according to District records.

“[Some] parents would rather see their child get an “A” in basket weaving than in an AP class,” said Black.

He made it clear that it is better to get a “C” or a “B” in a challenging course than to get a better grade in an easy class. Black believes the school needs to educate parents more on this topic

“A lot of the white people take classes together, like the AP classes,” said Jackson. “Unless you take a class with someone, you don’t really interact with them. This affects our bond as a school.”

Although social groups mix at U. City, and people don’t feel racial tension, there is still a separation that exists between African Americans and Caucasians, which can be clearly seen in the school cafeteria and in different level classes.

“I feel like one group doesn’t ostracize the other, but there’s more of a connection between people of a common race,” said Jackson.

1980’s Newspaper Interviews Reveal Little Change

While researching this story, extensive notes from interviews for a segregation article published in U. City’s school newspaper were recovered from an alumnus who was on the staff in the 80’s. In particular, interviews show that racial breakdowns are an issue that U. City has been dealing with for years.

One interviewee related the following: “I used to hang out with white kids, you know sometimes, when I was at Brittany and stuff, but now we don’t hang together because I’ve learned, you know, that like you talk to him, but you don’t go over to his house because he lives in a different neighborhood. It’s bad vibes. When you go to his neighborhood, you know, you look around, you say, ‘wow!’ you know, and you see white people just looking at you. You just won’t feel safe or secure unless you stay on your side of the line.”

A Caucasian student quoted in the recovered interviews describes how the only time she ever spent time with African Americans outside of school was after a musical.

These problems described by students who attended U. City in the 80’s are similar to the problems that those interviewed today describe. In addition, Black echoes the same sentiments when discussing segregation prior to the 80’s.

Moving Forward

“Something is not happening in the homes or in the schools, but this disparity cannot be allowed to continue,” said Black. “This country needs the best out of all our children and adults. Recognition is the first step with coming to grips with obstacles and problems.”

Black, who created the Academic U awards 25 years ago and was the president of U. City’s Parent Teacher Organization while his son was a student in U. City, continues to act as an advocate towards decreasing the achievement gap between African Americans and Caucasians.