Your donation will support the student journalists of University City High School - MO. Your contribution will go towards our young journalism events such as Media Passes, Sports Game Tickets, And equipment for our students.

COVID-19: not a ‘snow day scenario’

October 29, 2020

The snow day effect

U. City is never the first district to close when the weather gets bad.

When it snows, I look at surrounding districts like Clayton and Ladue first to see if they’ve closed. Usually, we follow shortly behind; usually, we follow suit. The school closings ticker in the bottom right corner of the FOX morning news broadcast will scroll to the left. If I see Clayton first, I keep my pajamas on.

Now, the only school closings relate to COVID-19, and as more and more schools in St. Louis County begin to reopen and welcome their students back into the classroom, this snowball effect—or more precisely, “snow day” effect—deeply concerns me.

I have kept complete faith in the school district and board since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and nothing has come about to sway my opinion. However, with county executives like Sam Page and administration in neighboring districts feeling the heat from obnoxious parents itching to send their kids back to school, it’s fair to say that most people are fed up with quarantine procedures.

And that is particularly unnerving. It’s not just the disease that is concerning; it’s the “normalcy” politics that are affecting the lives and well being of students, teachers and families. I’ve heard and read the stories of raucous parents incessantly berating their school districts to send their students back to class; I’ve seen the refusal and indignance to simple preventive measures like wearing masks in neighboring counties and even within my own community; I’ve felt the unease around COVID-19 fade into a general restlessness to return to normal; but, if anything, our circumstances are exponentially worse than they were when everything became abnormal.

Recently, despite rising infection rates, districts such as Clayton, Parkway West and Kirkwood announced their plans to return high school students on Nov. 9. Some neighboring districts like Brentwood have hosted fully in-person high school classes since the start of the school year, with varying degrees of success. U. City isn’t immune to the return-fever, either, and presented plans for kindergarten through sixth grade students to cautiously switch to a hybrid learning model starting Nov. 9, to then be joined by seventh and eighth graders on Nov. 30. At this time, there are no return plans for high school students, and—at least for the time being—there isn’t much incentive to do so anyways.

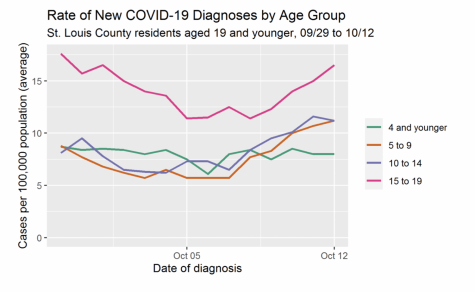

Most districts use St. Louis County age-demographic statistics to inform their decisions, and since October 8th, those statistics show a dramatic increase in new cases for ages 5-9, 10-14, and 15-19. Logically, it is impossible to understand the decision to start sending students back to school, especially as the weather cools and flu season creeps back into daily life. Experts have consistently warned of a massive second wave of COVID-19 occurring in the fall of 2020, but those warnings have apparently carried little weight. Furthermore, specifically within U. City Schools, distance learning is serving its intended purpose. A quick glance at the district’s COVID-19 Dashboard shows an all-time total of only 4 positive cases out of 2623 students. Taken together, distance learning—at least in U. City—is successful at limiting in-person interaction and thus the spread of the virus, even with rates rising significantly elsewhere in the county.

The trend of reopening is simply that: a trend. As districts feel more pressure to move their children away from distance learning alternatives, and as individuals grow increasingly agitated at home, the door is left open to a dangerously forced return. In response, as more schools bow to that process and disregard public safety, the likelihood that other districts will follow their lead increases.

The snow day effect is in full swing.

Peggy Halter, English teacher, hands out books to students in her literature classes during a drive-through school supply pickup in September.

A safer alternative

It would be downright irresponsible to send high school students back at this point. Even in Kirkwood, Parkway and Clayton, substantial backlash resounded from students surrounding the concerns of in-person learning during a pandemic, and those concerns are not confined to those areas. At a time when COVID-19 cases are surging—especially in high-school-age demographics—the choice of these districts to funnel their students back into a potentially hazardous environment makes absolutely no sense. The desire to achieve normalcy is never satisfied by jamming a warped version of reality—in this case, one that disregards prominent scientific research—down the throats of those who will be most affected. It is utterly foolish for those districts to succumb to the pathetic egging-on from complaining parents. It is fatally hypocritical for districts to push STEM fields onto students and then fundamentally ignore every aspect of evidence-based-thinking.

If COVID-19 is getting worse, why are we now deciding to take haphazard risks? It’s an issue that has been exacerbated politically and goes against every elementary fundamental principle that schools feed their students. We don’t manipulate the data to fit our hypothesis. We don’t ignore subsets of our population when we send out polls. So why are our leaders? Why am I afraid that the people in charge are more concerned about the opinions of the parents than of the students who will have to sit in class?

I won’t sit here and claim that online school doesn’t suck, but I certainly will not heed an inch to my own concerns about potentially going back into the building. I don’t feel good about it, and I know that most of my peers, when not overtaken by the crippling desire to feel connected to our school community, feel the same. I know how I am, how teenagers are. I see large gatherings of high schoolers on social media, birthday parties with maybe a single mask-wearing attendee, signs that people my age don’t care to take precautions. Beyond those conscious choices, I know peers who have to work through the pandemic at jobs where they interact with an enormous amount of people. I, myself, go out into public; I wear a mask, of course; I completely avoid crowds, even small ones; I only see one or two people with any regularity outside of my immediate family, I don’t eat inside of restaurants and I follow physical-distancing with anyone I don’t see daily. But even that, which represents a fairly conservative approach to a pandemic, presents a more-than-considerable approach to a pandemic when multiplied across an entire school population. I take all of the necessary precautions, but there are too many people to keep track of, too many potential sources of an outbreak, too many variables that make a return to school impossible to accomplish even relatively safely. Add in the fact that teenagers are notoriously guilty of flouting guidelines and it’s not difficult to see the problem with shoving high schoolers back in school prematurely.

Ultimately, this pandemic and the resulting solutions rest on the unknowns, and there are far too many to feel confident in a return plan. One of the largest criticisms from returning students to their districts was a lack of communication between the decision makers and those affected, and U. City students certainly can relate to that. Even with no plans for returning on the horizon, the criticism sourced from other high schools offers a unique opportunity for our own district to do better, and they can start by hearing student concerns surrounding distance learning. Many students, myself included, feel overwhelmed and drained from virtual learning, but recognize that it is the only truly safe option. I haven’t talked to a single person—student or teacher—who doesn’t feel that their workload has increased significantly online than it is in person. We have to stay in the same setting for work all day. Our once bustling and stimulating school days have been replaced with mundane, blue-light simulations. I also haven’t talked with anyone so adamant about going back that they feel these issues are without solutions—and that is why we need our input to be heard. We don’t want to go back, we simply want our concerns about distance learning to be listened to and addressed. Since the first week of school, students have not received a single survey from any district or school administration, which is—quite frankly—unacceptable. If students are taught how to persevere through challenges in the classroom, then the adults in charge of the standards for learning need to adhere to the same principles. A plan is never perfect; it requires constant attention and attending to. Our current learning model is far from perfect, but it would likely benefit from a conscious effort to recognize its issues.

I am confident that if distance learning was tweaked to better suit the reservations of those within it, there would be no need to return to school. Therein lies the key point. These circumstances are not about what everyone wants—because we all want to go back to normal. It’s about what we need to do—and right now we need to continue on the path we’ve set out upon and improve the quality of online education.

A message for our leaders

To our school district, administration, and school board: do not send us back. Continue to look at the scientific data. Continue to be better than our neighbors. Don’t succumb to normalcy politics. Don’t neglect the importance of iterative design with online learning. Keep us safe; because now is not the time to take any risks, even calculated ones. Listen to our concerns and work with us to calm them. Do not fail us.

As the district dominoes continue to fall, we have an awesome opportunity to set an example and become a leader in education and community. We don’t have to listen to selfish “send them back” sentiment. We don’t have to take risks. We can stay online and make the necessary adjustments and successfully educate 100%—not 90%, not 95%, not any other arbitrary percentage—safely. If our own board meetings aren’t held in person, why should we force our classes to be?

I trust the leaders of my community; I trust that they know it isn’t safe to send us back; and I trust that they will learn from the mistakes of fellow districts—that we will be better.

Kirby Miller • Nov 8, 2020 at 11:49 AM

I go to Clayton. The key is I can’t do online anymore. I know this is not related to the cova but I had an internet crisis with the internt kicking me out of my 2nd hour class 7 times in 16 minutes. I gotta go, period! Overall, you have such a good tone to prove for your school that you need to make the right choices, and when we go back tomorrow there is a set of rules we will follow too, and that is wearing a mask at all times, go directly to classes as you transition, don’t go into the classroom until all students from the previous period, staying in your assigned seat and not getting up, etc.

Mary Nani Lhotak • Oct 30, 2020 at 9:29 AM

I appreciate this strongly worded editorial and the wisdom it contains. The employees of the district, students and all the community that interacts with them are at risk by any return to indoors and contact. It is wise to protect our greatest assets, the humans.

The compounding societal causes of race based healthcare disparities — systemic defunding, racism and whitesupremacy — greatly effect covid morbidity for Black people and make these decisions from Dr. Hardin Barltey even more vital to Black families and our entire communitys’ wellbeing.

Bishop Luther D. Baker • Oct 29, 2020 at 7:51 PM

You really spoke TRUTH to the POWER in your editorial. Our superintendent and administrators are doing an awesome job in keeping the students, staff and school community of the SDUC safe and informed. Sometimes you have to do that which you know to be the best for you. Being a leader isn’t easy. It comes with challenges and push back from many angles. The beauty of it is when you take into consideration the beginning, middle and end and the decision made pan out to be the right one. You can rest and look at all the naysayers and say…..I MADE THE RIGHT DECISION. I have total FAITH in Dr. Hardin-Bartley and the administrators of our district that they will continue to navigate us through this challenging time. In the meantime may we stay unified as a community and U.CITY STRONG! Truly we are all in this together and will come out on the other side greater than before.