The directive couldn’t have been clearer: “All electronic devices are prohibited during school.” Research supporting this stance couldn’t be murkier, however. Other than data from surveys on cell phone use at school, almost no studies have addressed the impact of students’ use of electronics on academic performance.

In general, policy options are to ban cell phones entirely, allow their use only during non-instructional times, or encourage using them as instructional tools. Research indicates that parents are often adamant supporters of their children being allowed to use cell phones at school, but teachers overwhelmingly favor a ban. Ms. Nevils is no exception and states her case succinctly, “The classroom and the building are a professional learning environment and should be treated as such. There is no cause for students to make or receive phone calls in the classroom.”

Personally, I think the ban is a logical consequence to last year’s more permissive policy. Being able to use phones and iPods during hall passing between classes and at lunch seemed fair and reasonable. Most students adhered to the rules, but this privilege was overtly abused by many. Not only did phones alert in class, but kids had the audacity to answer them and act like their gossip of the minute trumped the goal of the class.

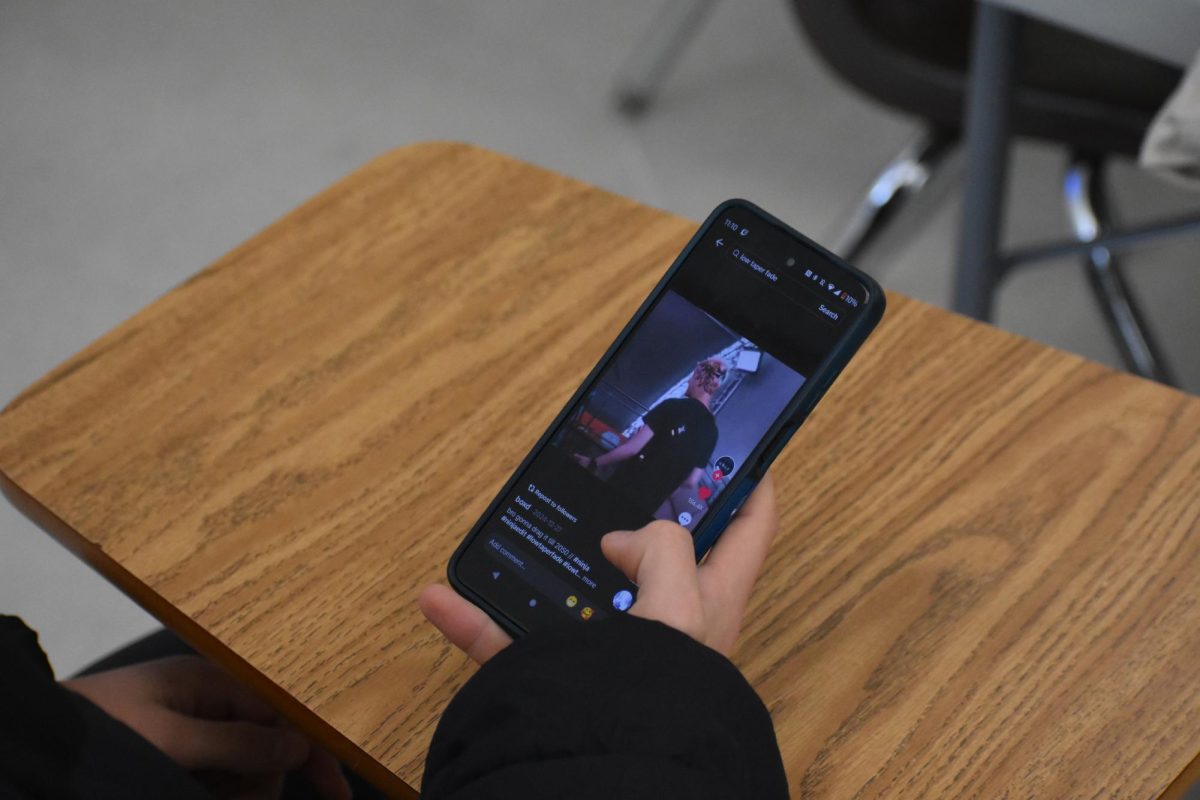

While the ban may feel like proper retribution to teachers and administrators, it is unlikely to be successful. According to Common Sense Media, when cell phones are required to be turned off, stored, or banned, 66, 57, and 63 percent of teens, respectively, use their phones anyway. These statistics shouldn’t be surprising, considering that some teens talk or text while driving, when the stakes are much higher than any punishment a school disciplinarian could mete out.

A report from Common Sense Media called for schools to redesign education to include digital literacy and citizenship. They want students not only to become skilled at accessing information, but also to learn responsibility for both the content of their communication and their actions when using any form of digital media.

In addition to learning the social etiquette for use of cell phones and other electronic devices, students and teachers could take advantage of some of the other features these devices offer. Listening to positive and energetic music, for example, can improve students’ performance – the so-called Mozart effect In another report from the New York Times, English language learners were able to move out of bilingual classes years sooner after studying lyrics and listening to English songs on iPods. Thus, it seems we are under utilizing the positive power of electronics that could improve vocabulary for SATs or aid foreign language instruction.

Rather than become complacent and declare victory, our teachers and administrators need to rethink the ban on electronics. The solution should allow students to reap the benefits from academic engagement that use of electronics can foster. Deterring illicit use should involve high-tech interference or network monitoring, instruction on ethical use of digital media, harsh penalties for violations, and relinquishing devices for examinations. It sounds complicated but is more realistic than a head-in-the-sand ban.